This article is out of order with the planned series on my garage remodel and subsequent installation of pneumatic systems and CNC mill. I promise I’ll get back on that, but this was posted at the Saunders Machine Works forum and I might as well post it here as well so you can see more of the photos & video I took along the way.

Problem: I put Gladiator Geartrack slat wall panels around my garage to help get things up off the floor without making holes in the walls. The wall panels, hooks and shelf modules are a bit pricey but occasionally they go on sale, and they make it easy to organize things, and more importantly, re-organize things when you need to rejigger things to make it all fit.

But some things just don’t work. Bar clamps are an example. If I purchased hooks for each clamp I own, I’d be out $150-200 at the very least, and it would use the space inefficiently. Now I could go and lag some inexpensive pieces of pine or maple into the studs in the walls and make a clamp rack in the corner of the garage where I plan to put them. And I probably won’t move them once I’ve done it. But the slat wall makes moving stuff around easy, so as the garage gets revised (which has been continuous), rearranging things to fit the space available will be necessary.

So I needed some sort of bracket that would allow me to screw things into it, then hang it on the slat wall.

I use a lot of 80/20 extrusions around my shop. My Tormach enclosure is made from the 10 series stuff. My TTS tool racks (below) are made from 1020 extrusions and some cheap desk grommets from Amazon. So I use 1/4-20 screws all over the place since they are compatible with this type of extrusion. And as I add to the slat wall I’ll be using it for hanging air regulators and oilers and the like as well as I expand that system. So some sort of matrix of 1/4-20 screw holes similar to a fixture plate made sense.

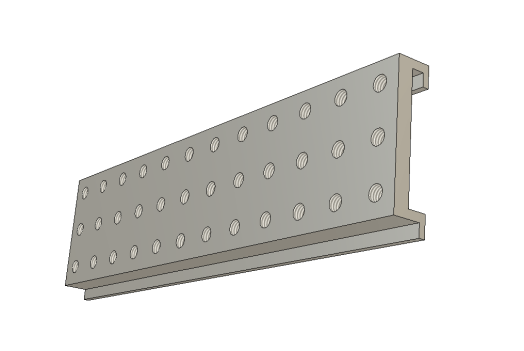

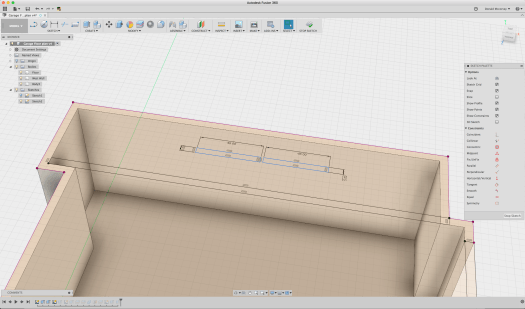

The first picture (below) is the F360 model of the matrix bracket – 12×3 7/16-14 screw holes on 1.125 spacing on center. Why 1.25″? Because my miter saw has a 1/8″ kerf and I planned to cut this up into 1″ wide pieces. (I’m reconsidering this spacing to make it more 80/20 10-series friendly, but that means saw cuts result in a <1″ part, so it’s up in the air at the moment) The 7/16-14 holes support use of a 1/4-20 threaded insert, so making the threads stronger and more durable becomes straightforward, but I can still use a 7/16 screw if that makes sense.

The next problem was work holding. I have a pair of GMT 6″ vises, but the blank is a bit over 14×3″ and the part is perched on top. Moreover, since I’m near the work envelope limits of my PCNC 1100, and I had a drilling operation with a large Jacobs chuck, supporting the blank in a conventional vise didn’t seem like that good an idea.

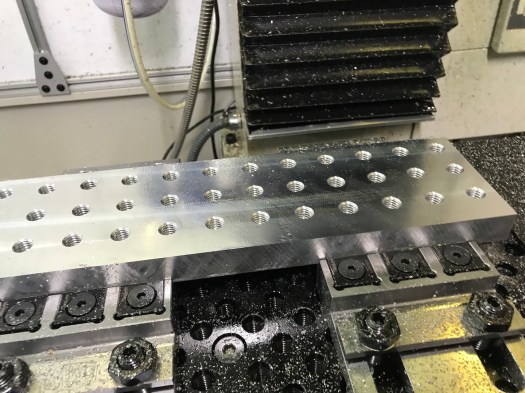

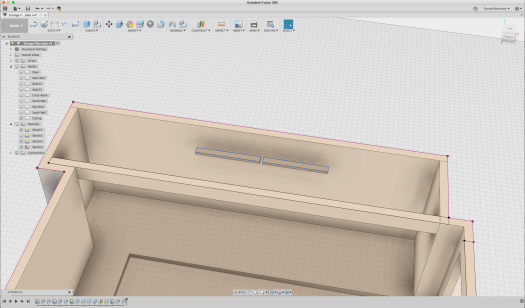

In February of 2018, I attended Saunders Machine Works’ Workholding and Fixturing class. John had already introduced his line of Mod Vises, which were interesting because a pair of mod vises would allow me to get the workpiece down near the fixture plate, leaving more room for the Jacobs chuck, and making everything a lot easier to see. Well almost (tale of woe to follow). You can see what I did in Picture 2.

Let me preface the next part of this story by pointing out that (a) I’m an electrical engineer and (b) I generally assume I’m an idiot on anything outside my specialty, so I have to learn, usually the hard way. I have a nice collection of Haimer tips and busted end mills (and one thread mill) as a evidence of this school-of-hard-knocks approach.

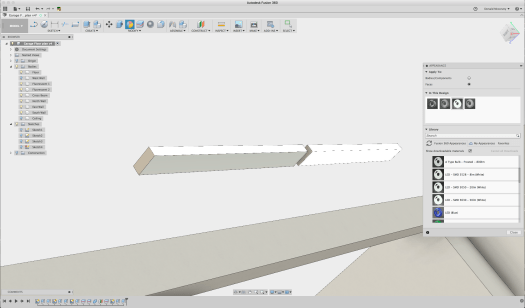

Making the field of screw holes was almost old hat (picture 3). I’ve used thread mills before and the only real problem was figuring out why my 7/16-14 screw threads did not accommodate 1/4-20 threaded inserts. To make a 7/16-14 thread, you first start with a U size drill, then thread it with an offset of 0.0802 and a 0.300″ diameter thread mill. And those of you who have worked with threaded inserts will immediately realize my error. If I read the spec for the insert, it requires an X diameter drill (0.397) because the insert does not have full-depth threads on it. Every hole, therefore, was wrong. I was able to fix this with my trusty 0.5 x 1/4″ LC VF stub end mill and milling out each hole to a minimum diameter of 0.397. Voilà! The inserts fit perfectly. If only that was the end of the tale…

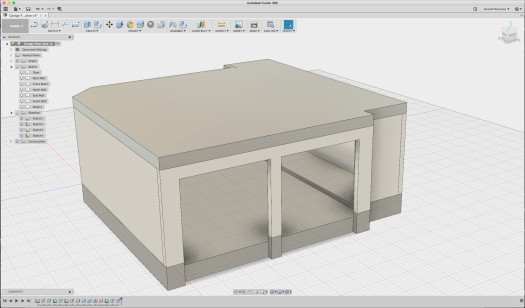

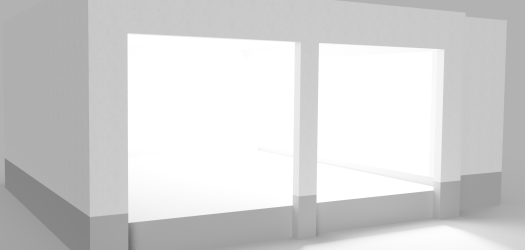

So you practiced machinists will see almost immediately that when I set the CAM to hog out the flange on the bottom edge of my part on one side, held in place with Carr-Lane Tiny Vises and on the back side by steel clamping bars that came with the fixed jaw of the SMW Mod Vises. Add in a 1/2″ LC Variable Flute End Milland a dash of stupidity in the form of a common bottom level for a 2D contour operation on front and back and you get the result in picture 4 and picture 5, along with a lot of consternation over picture 6. (Yes, that’s a 1/2″ Lakeshore Carbide variable-flute endmill, which had a tragic, short life of about ten seconds)

The second op I saved for the next day. I’ve used a shear hog before, but I couldn’t recall for the life of me what the correct woc/doc was for an 1100 in 6061. So it took a few tries to get a workable combination. There’s a pretty good divot missing from the back side (where no one will ever see it!) now, but the end result was satisfactory and since I’m the customer, only I will know about it (and anybody else who reads this for its comic value). You can see some of this the video below:

Yes, I know I need to increase the non-cutting feed rate. This was just the first try and right off hand, not breaking things was more important than time.

Surface finish wasn’t bad – I have some tweaking to do because something is off somewhere and my horizontal clean-up op did pretty much nothing (seems like the tool offset on the shear hog is a bit too deep) – so I pressed on.

The last tense operation was doing something new for me – using a 7/32″ thick key slot cutterto make the slot in the upper flange of the bracket. I probably ran too many passes and could have made them much deeper, but at this point, taking light cuts (with a HSS cutter) seemed a good starting point. Mostly I was concerned that the woc was going to result in rubbing on the cutter shank on the final pass at full depth. But as you can see in the video below, this was unfounded and it worked just fine.

After a quick deburring with my chamfering tool and a few passes on the scotch-brite wheel, you see the final result in picture 10. Picture 11 (photo below) and picture 12 show the slices of this panel having been cut off using my miter saw, which worked out better than I had expected. I cleaned them up on the scotch brite wheel and threaded inserts added as a final step.

Hope someone finds this useful.

Photos: Tormach

Photos: Tormach Photo: Tormach

Photo: Tormach